This time last year, I was in New York City, getting ready to ring in a new year, like I had (at rough count, at least three or four other years this decade), at Madison Square Garden, watching, singing, and dancing to a band I loved. Champagne drunk at midnight, I had no idea, as My Morning Jacket launched into Kool & the Gang's "Celebration" (always a personal fave), what I'd face this year. I had no idea my natural breasts were bouncing and jiggling to the beat for the last time, that by the end of the year, they'd be gone.

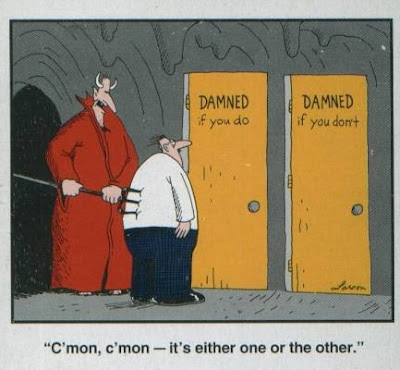

The year that began in the early morning in Manhattan took me many unexpected places -- to Belize, to Costa Rica, to Cape Cod, and many places in between -- but none so unexpected as the operating room where I traded in my breasts for a chance to ring in many more new years cancer-free. 2009 has been, by any estimation, a year of tumult: first, my husband got a new job, moving from college professor to college administrator, and lengthening his commute from two blocks on foot to 45 minutes by car; then, the crushing news of being BRCA+, the anger, the sadness, the decision; then, our first wedding anniversary, clinking glasses at the bar of the hotel where we'd spent our first night as husband and wife, incredulous that so much could have changed in so short a time; next, our first home, a place we'd live, we hoped, in good health for many years; and then, my double mastectomy. And in the end, we'll remember 2009 as our BRCA year. Four little letters that meant nearly nothing to me a year ago have, in twelve short months, changed my life, my husband's life, my family's lives irrevocably. Everything is different now. Not even my boobs are the same.

Needless to say, I'm anxious to ring in a new year. I have no idea what 2010 has in store for us, but I can only wish it's less eventful than 2009. Please, no surprises, nothing major. Just twelve months free from drama. Tonight we will welcome the new year with friends we didn't know this time last years,friends we've made because of BRCA, friends who've shown me what life looks like as a previvor, friends who have stood by my side through surgery. It's a far cry from the frenzy of a rock concert at MSG, but it's a fitting way to see the year out.

Year-end lists are a popular (and gimmicky) way to sum up what has come before, and in that spirit, I'd like to offer my own: My top 9 blog posts of 2009. I began writing in March, even before I had my genetic test results, and the solace and catharsis that has come from writing here has helped me inestimably. I hope that it has helped other, as well. So, without further delay, my top 9 of '09:

9. Sorry, can't talk. I'm on my way to a cancer appointment

(March) In which I am genetically counseled

8. It was the breast of times, it was the worst of times

(April) In which I come out to friends (and the internet) as a mutant

7. The picture of health

(May) In which I have an MRI

6. The view from the other side

(June) In which I watch a good friend recover from a preventative mastectomy

5. Sky Rockets in Flight, Cape Cod Delight

(July) In which I spend an afternoon with a dear friend recovering from a rare cancer and wonder why I have a chance he never did

4. Previvors vs. Survivors in the World Series of Love

(September) In which I talk about how hard it is to be a previvor

3. The Keynote Speaker Has Left the Building

(October) In which I become a BRCA spokesperson

2. (Don't) Say (Just) Anything

(October) In which I offer the "Top Ten Things Young Previvors (Probably) Don't Want to Hear, and the Top Ten Things We (Probably) Do"

1. A Break Up Letter to My Boobs

(December) In which I say goodbye to boobs

Wishing all of you a very happy and healthy 2010! See you next year!